Mama Cooper and Creedence: A Musical Journey

It’s a Saturday afternoon and my 11-year-old granddaughter and I are driving down a backroad singing along with Creedence Clearwater Revival from her iPhone. Devanna knows all the lyrics, and I can join in on the choruses. There’s a Bad Moon A’Risin’, I’m belting out in my best imitation of John Fogerty.

Devanna is a bit surprised that – at my advanced age – I know anything at all about Creedence, or any other musicians you might call “cool.” And I’m a bit surprised that an 11-year-old is into all that great music from the 60’s and 70’s. But we grin at each other and keep belting. I Heard It Through The Grapevine. Which, as a former newsman, I’ve always considered a perfectly good way of disseminating information, especially when it comes to being jilted by your honey.

I tell Devanna that my musical tastes gallop off in a thousand directions at once. I love and appreciate rock, country, folk, classical, jazz, gospel, anything that has good lyrics and a decent melody and beat. I’m partial to Fleetwood Mac and the New York Philharmonic, Willie Nelson and Thelonious Monk. My automobile is pretty much basic transportation, but it does, by golly, have satellite radio.

Where did this musical eclecticism come from? I’d say it began with my grandmother, Mama Cooper, who was a piano teacher in my Alabama hometown. When I was old enough to sit on the bench of the Story & Clark in her parlor, she started teaching me. I stayed with it until I was old enough to chase girls, but by then, I knew the basics of how notes go together to make a composition, which key had three flats, and how 4/4 time differed from ¾. And I had a growing notion that you didn’t have to be stuffy about your tastes, that there was all sorts of good music out there, in all sorts of genres.

My immediate family enjoyed music. Mother played the piano, Dad had a nice baritone voice, and on family trips, they and we four kids sang a lot. Down By The Old Mill Stream, Where I First Met You, With Your Eyes So Blue, Dressed In Gingham Too, etc. etc. I played baritone sax in the high school band and sang in the choir at Elba Methodist. And I launched my broadcasting career as a teenage disc jockey at WELB, the Mighty 1350, playing everything from Ray Charles to The Florida Boys. After that, I disc jockeyed my way through college in Tuscaloosa.

Fast forward to 2002, when I had an idea for a story that seemed to work best on a live stage. Not only that, I started hearing original songs in my head, and they seemed to play a central role in telling the story. And so “Crossroads” was born. I remembered enough of those basics from Mama Cooper’s piano lessons to put notes on paper and flesh out the words and melodies. A fantastic composer, Bill Harbinson, took my hen scratching and turned it into a wonderful musical score.

The play sold out 26 performances at a professional theatre in Blowing Rock, North Carolina and launched my career as a playwright. Seven other plays followed, one of them another musical, “The Christmas Bus.” They’ve all been published and are performed by theatres across the country.

So yes, Devanna, I know a little bit about a lot of music. Enough, you might say, to be dangerous. I can sing the chorus to Bad Moon Risin’ and I can hum the melody to Symphony Pathetique. It’s all in my head and it enriches my life in ways more numerous than I can count. It can summon all of the human emotions, and maybe some I never imagined before. I recommend it as an essential part of the human experience.

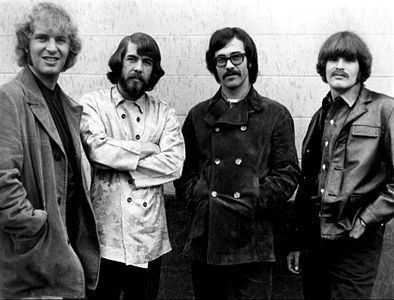

Thank you, Mama Cooper. And thanks, too, to Creedence.