The Danger of Saying Too Much

In my previous life as a television person I was fortunate to work with people with far more experience and wisdom than I, and I tried to learn from them. Two in particular stand out because of the way they approached their jobs.

Clyde McLean was the long-time weatherman at Charlotte’s WBTV. He wasn’t a trained meteorologist, he was an announcer who did the weather at 6:00pm, but his many years observing and reporting on the weather in the Carolinas made him vastly knowledgeable. His trick was, he didn’t burden the audience with that vast knowledge.

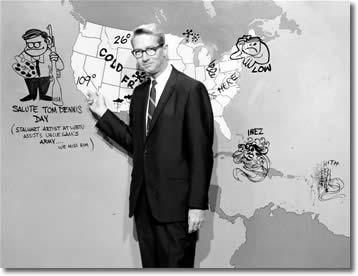

Clyde told the story of the elementary-age kid who had to do a report for class on weather. He went to his father. “Dad, what’s weather?” Dad replied, “Go ask your mother.” And the kid said, “I don’t want to know that much about weather.” Clyde took the same approach. He figured if you tuned in at six o’clock, you wanted to know the basics. Rain or shine, sleet or snow, fair or foul? Clyde worked in the days before fancy computer-generated graphics; he physically drew on a big map with a marker, showing you troughs and fronts, high and low pressures. But he never over-did it. He stuck to the basics. Here’s what it looks like tomorrow, and the next few days after that.

Clyde knew that weather forecasting, especially in the years before a lot of satellite stuff and computer modeling, was an approximate thing. He loved to tell the story of the winter night when he predicted partly cloudy skies for the next day, only to get a morning call from a fellow who said, “I’ve got six inches of partly cloudy in my front yard.”

The other colleague who comes to mind in this regard is Jim Thacker, the best television sportscaster I’ve ever been around. Jim not only anchored the sports desk for WBTV, he was – along with superb analyst Billy Packer – the play-by-play man for ACC basketball, and a regular on CBS-TV’s coverage of pro golf, including the Masters Tournament. I once sat in the tower with Jim as he worked a tournament in. He was first of all meticulously prepared. He had constantly-updated note cards on every PGA player. He knew the course like the back of his hand. But his genius, I think, was in knowing what not to say. Jim told me, “Never tell the viewer something they can see for themselves.” Like Clyde McLean, he never over-did it.

I’ve been thinking about Clyde and Jim as I’ve watched college football bowl games the past few days, and thought how the announcers violate their principles ad nauseum. The play-by-play guy tells us everything we can see for ourselves, and the analyst rattles on about the intricacies of the game that add nothing to our enjoyment of the action. They just can’t seem to shut up. And it’s not just in college football. A few announcing teams across American sport get it right – i.e. Jim Nantz and his crew at the Masters – most don’t. Thank goodness for mute buttons on our remotes.

I try to apply Clyde and Jim’s wisdom when I write. I’m a firm believer in the idea that less is more. Words are the waves on which a story rides, and if I pile on too many words, the waves get choppy, and pretty soon you’re more concerned with the chop than the story. My job is to give you a few hopefully well-chosen words to trigger your imagination, and let you become a partner in the story-telling. Like Clyde, I need to keep the details at a minimum; like Jim, I need to let you see for yourself. I need to know when to just shut up.

Another role model is Ernest Hemingway, who once said, “I know the twenty-five cent words, therefore I can use the nickel words.” I like nickel words, and as few of them as absolutely necessary. I wish sports announcers did too.